Episodic Pelvic Pain

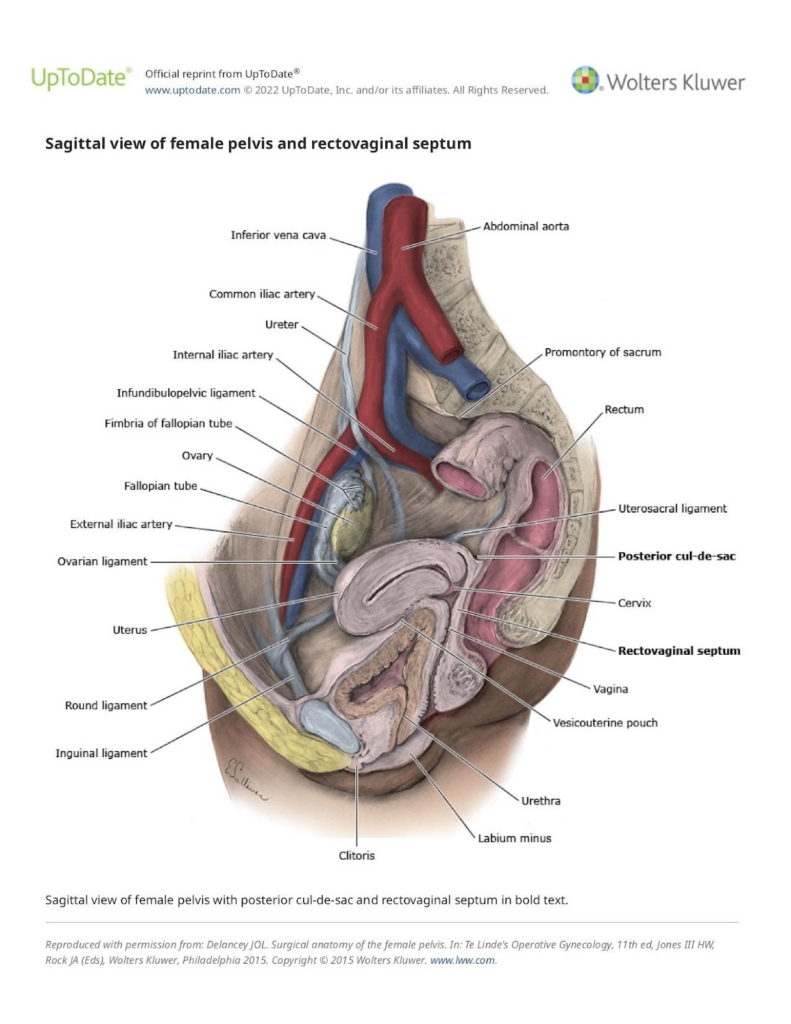

The pelvic region of women is a complex area both physiologically and anatomically. A lot of critical and sensitive bodily structures and functions reside in the lower abdomen and groin. These include important organs of the female genital system as well as those of the urinary, gastrointestinal, nervous, and blood vessel systems. Abnormalities of any of these systems can be associated with pain. Therefore, the list of potential causes of pelvic pain in women is long. See the image of the female pelvis below.

The evaluation of pelvic pain can be complex and requires a careful patient history and physical exam. Questions on the history include what is the specific location and character of the pain and is it related to other functions and events like the menstrual cycle, bowel movements, urination, body movement, and sexual intercourse? What tends to aggravate the pain or to make it better? How long has it been going on and is it trending worse or better with time? Very importantly, how is it affecting the patient’s quality of life? Does it prevent desired activities or interfere with sleep?

A careful physical examination addresses further questions. Where on exam is the pain recreated or elicited? Is it more related to the regional muscles or to the underlying internal organs? Do certain positions either aggravate or alleviate the pain? The doctor can examine for tender nodules that are characteristic of endometriosis, tenderness to motion of the uterus that can mean infection or scar tissue, or for cysts and growths. The external genitalia and the vagina can be visualized for sores or evidence of infections.

Sometimes, imaging studies, such as pelvic ultrasound or, less commonly, MRI are useful to diagnose the source. Other times, depending on the symptoms, the gynecologist might refer to and work in concert with other physicians such as urologists or gastroenterologists.

An important early goal of an evaluation for pelvic pain is to identify the source and to rule out occasions when the cause might be a medical condition that presents immediate danger, such as a serious infection, malignant tumor, or tubal pregnancy.

The good news is that a treatable source can be identified and corrected in most cases. This may include, for example, antibiotics for milder pelvic or urinary infections, hormonal therapy for bothersome menstrual cycles, or pain medication to help while the body absorbs a benign ovarian cyst.

In all cases, excellent communication between the patient and doctor is a must. The doctor should listen attentively, accept the patient’s perception of her pain, not diminish the reality of the suffering, and work to alleviate the pain.

Chronic Pelvic Pain

In some cases, no immediate specific cause for pelvic pain is identified. When this occurs, especially when it is not menstrual cycle related (which is called dysmenorrhea) and has persisted for more than three to six months, it may be termed chronic pelvic pain. This is often a severely frustrating condition because of the long-term disruption of quality of life and the lack of a satisfying answer regarding the cause.

Management of chronic pelvic pain requires an open and trusting relationship between the patient and the care provider. The patient must keep track of her symptoms and feel free to report them. The doctor must listen non-judgmentally and hear the complaints at face value. Together, they develop a treatment plan that strives to maximize the patient’s quality of life and thoughtfully balances the benefits versus the side effects and risks of therapy.

Which treatments are effective varies with each patient and the course is often one of trial and error, starting with the easiest to manage methods. Thus, accurate feedback from the patient and careful listening from the doctor are paramount. Other providers might be consulted, such as physical therapists or pain management specialists.

Psychosocial issues may be important in the evaluation and management of chronic pelvic pain. It is well known that many chronic pain conditions, including of the pelvis, are associated with, or may be aggravated by elements of depression, anxiety, and stress. This is not surprising considering that chronic pain, especially without a clear cause, can promote any of these.

This never means that the pain “is all in your head.” The pain is very real. But it does mean that evaluating for these elements and possibly treating them is often an important consideration for helping to relieve chronic pelvic pain. Survey type questionnaires may be administered. Sometimes, consultation with a mental health professional is obtained.

Summary

The evaluation and treatment of pelvic pain in women can be complex because the region has many structures and functions that can be the source. Most of the time, there is a benign cause that improves with time or can be readily treated. It’s important to initially rule out the occasional medically serious cause and always to provide relief from pain and the fulfillment of a good quality of life.

Pelvic pain that persists more than three to six months and doesn’t have a readily identifiable focal cause is called chronic pelvic pain and can be a frustrating and important problem. Management requires a solid and trusting patient care relationship, patience, often trial and error, and sometimes outside consultation.

Please call 919-916-3333 for further information or to schedule an appointment.

Note: Pelvic pain is a complex topic with great variation among individual patients. It cannot be comprehensively covered in this format. The above is for informational and orienting purposes and to attempt to describe the approach of this gynecology practice.